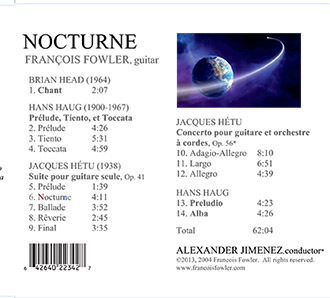

Nocturne (2004)

Track Listing

BRIAN HEAD (1964)

1. Chant ![]() (MP3) 2:07

(MP3) 2:07

HANS HAUG (1900-1967)

Prélude, Tiento, et Toccata

2. Prélude 4:26

3. Tiento ![]() (MP3) 5:31

(MP3) 5:31

4. Toccata 4:59

JACQUES HÉTU (1938)

Suite pour guitare seule, Op. 41

5. Prélude ![]() (MP3) 1:39

(MP3) 1:39

6. Nocturne 4:11

7. Ballade 3:52

8. Rêverie 2:45

9. Final ![]() (MP3) 3:35

(MP3) 3:35

FRANÇOIS FOWLER, guitar

ALEXANDER JIMENEZ, conductor*

Concerto pour guitare et orchestre à cordes, Op. 56*

10. Adagio-Allegro ![]() (MP3 - 4:32) 8:10

(MP3 - 4:32) 8:10

11. Largo ![]() (MP3) 6:51

(MP3) 6:51

12. Allegro 4:39

HANS HAUG

13. Preludio 4:23

14. Alba 4:26

Total 62:04

CD Liner notes

“Ses enregistrements de mes deux oeuvres, la Suite pour guitare Opus 41 et le Concerto pour guitare et orchestre à cordes Opus 56 révèlent chez l’interprète un sens solide de la structure et du phrasé allié à une grande sensibilité musicale, le tout soutenu par une excellente technique instrumentale.”

“His recordings of my two works, the ‘Suite for guitar, Opus 41’ and the ‘Concerto for Guitar and String Orchestra, Opus 56’ reveals in the performer a solid sense of structure and phrasing allied with a great musical sensitivity, all of this supported by an excellent instrumental technique.”

- Composer Jacques Hétu

Music by American composer Brian Head, Swiss composer Hans Haug, and Canadian composer Jacques Hétu. Featuring a re-issue of the 'world premiere' recording of the Concerto for guitar by Jacques Hétu, solo guitar pieces by Swiss composer Hans Haug, and a unique miniature by American composer Brian Head (Chant found in Scott Tennant's popular guitar method Pumping Nylon).

CHANT

Brian HEAD

Composer Brian Head was born in Washington, D.C., in 1964. He presently resides in Los Angeles where he teaches both composition and guitar at the Thornton School of Music, University of Southern California. His works have been recorded and performed frequently throughout the United States and abroad.

Chant was inspired by one of Head’s own orchestral compositions of the same name. A remarkable guitar miniature, hardly two minutes, Chant vacillates between moments of brilliance, lament, and quiet reflection. Throughout the piece, the composer draws upon the technique of tremolo, though his use of this often-employed guitar effect is quite unusual. In the method Pumping Nylon, guitarist/author Scott Tennant points out that the work “is unique in that the notes often change in the middle of the tremolo, thus creating a constantly fluid line.” [ i ] Head explains that:

This incarnation for guitar was composed as a tremolo study (tremolo being a technique in which the right-hand thumb plays a moving bass line and the first three fingers work quickly in succession to sustain a melody). The traditional tremolo functions of the thumb and fingers are blurred in this work to create alternating contrapuntal and scalar passages. Some have suggested that the piece was conceived as a Celtic caoine (a death lament), a monophonic wailing that is a part of the style of singing known as sean nos. Others have remarked that it resembles the flamenco cante jondo. While I welcome these interpretations, my more direct inspiration was the chanting of Baha’i sacred writings in Farsi and Arabic. The close resemblance of these three diverse sources is striking, and while I didn’t mimic these styles, I certainly attempted to reflect some remnant of their transfixing depth of expression.

PRÉLUDE, TIENTO ET TOCCATA – PRELUDIO – ALBA

Hans HAUG

Hans Haug (1900 – 1967) was born in Basel Switzerland on July 27, 1900. Throughout his career, along with composing, he was quite active as a conductor, teacher, and musical director. Appearing as guest conductor all over Europe, he also held several conducting positions in his native Switzerland, including the Basel Municipal Theatre (1928-1934), the Interlaken Kursaal, and for Swiss Radio in Lausanne (1935-8) and Zurich (1938-43). Though much of Haug’s teaching activities were done in Switzerland, he also worked as a guest lecturer/instructor throughout Europe.

In 1961, the legendary Spanish guitarist Andrés Segovia invited Haug to teach some composition courses at the summer music academy in Santiago de Compostella, Spain. It is here that Haug completed his Prélude, Tiento et Toccata [ii]. Among Haug’s first compositions for guitar were Preludio and Alba, composed in the early 1950’s. In 1961, Segovia reversed the ‘implied’ order of the two pieces, recording them as Alba and ‘Postlude’ [iii].

A very comprehensive catalogue, Haug's compositional output includes string quartets, various chamber works, vocal music, concertos, symphonic works, operas, oratorios, and film music. Though not best known as a guitar composer, his works for guitar are quite numerous, including: Concertino pour guitare et petit orchestre (quasi una fantasia) (1951), Concerto pour flûte, guitare et orchestre (1966), Fantasia pour guitare et piano (1957), and Capriccio pour flûte et guitare (1963) [iv]. Recently, manuscripts of unpublished solo guitar works were found in the Segovia Archives, including Etude (Rondo fantastico) (1955), and Passacaglia (1956) [ v ].

Though the Haug pieces on this recording may not exhibit the contrapuntal inventiveness evident in the guitar works of Jacques Hétu, there remains a beautiful expressive quality in these selections, and a wonderful sense of harmonic and melodic unfolding. In some ways, Prélude, Tiento et Toccata, Preludio, and Alba are written within a language that guitarists might refer to as ‘Segovian’ neo-romanticism, notably, the overall lyricism and autumnal melancholy of these works.

SUITE POUR GUITARE SEULE, OP. 41 -- CONCERTO POUR GUITARE ET ORCHESTRE À CORDES, OP. 56

Jacques HÉTU

Jacques Hétu is one of Canada’s most respected and successful composers. His compositions have attracted interest from notable musicians such as Glenn Gould, Charles Dutoit, Pinchas Zukerman, and Kurt Mazur, who have performed, and recorded his music. His works are regularly performed within Canada, the United-States, Europe, Japan, and South America, and he has been composing commissioned works for nearly four decades. In 2000, Hétu retired from his teaching position at the Université du Québec in Montréal. He now resides just outside of Montréal and continues to maintain a very active composing schedule.

Hétu’s compositions encompass many genres, including four symphonies, and concertos for bassoon, clarinet, flute, trumpet, trombone, piano, organ, guitar, and a double concerto for piano and violin. He has also composed several instrumental solos, chamber pieces, and works for voice and orchestra including Les clartés de la nuit, Les abîmes du rêve, an opera (Le Prix), a mass (Missa pro trecentesimo anno), and music for a film (Au pays de Zom).

The elements of Hétu’s style have been defined as a combination of neo-classical forms and neo-romantic expression with a musical language of twentieth-century techniques [vi]. The Suite and Concerto are characteristic of Hétu’s treatment of melody, harmony, and form. It is music that is deep in its structure, outwardly dramatic, but also possessing a seemingly infinite amount of nuances and subtleties.

The Suite pour guitare seule, Op. 41 was composed in 1986 and represents Jacques Hétu’s only work for solo guitar. The composition was commissioned in 1986 and recorded in 1991 by Uruguayan/Canadian guitarist Alvaro Pierri. In Soundboard [vii] David Grimes gives a brief but illuminating description of the Suite:

This is thoughtful and serious music that will require probing musicianship and careful listening. There is more here than is apparent to the casual observer… The five movements are well contrasted in mood and texture. The Prélude has an almost-unbroken flow of sixteenth notes, with the natural stress points outlining melodies and producing rhythmic interest. The Nocturne creates a mood of wee-hour solitude and latent mystery. In the Ballade, the rhythms become more driving, and the movement builds gradually to a peak of intensity before descending again. The Rêverie is spacious and pensive. In the Final, the appearance of the score is rather innocent, but there is quite a bit of cumulative power, and the effect is bold and passionate

The Suite illustrates Hétu’s economical use of musical material as well as his tendency to present the primary melodic and motivic ideas of a piece within the introductory measures. In a 1988 interview with Renée Larochelle for Radio-Canada (ACM 31), the composer explains:

And when it comes to writing, it always starts with a melodic idea. I am still a melodist. There is always a theme, short or long, but which contains in embryo the elements for creating the entire work… That’s all there is to it. But once the inspired idea has been adopted, the real work begins, the work of composing. And this time 5% of inspiration, which is absolutely essential, will give birth to the 95% to come. On condition that one is satisfied with that initial idea.

The first measure of the Prélude from the Suite pour guitare contains virtually all of the musical material to be used throughout the movement. To varying degrees, this type of germinal approach is evident in all five movements of the Suite. For example, in the Final, all the material used in the piece is derived from motives found in the first four measures. In the Rêverie, the interval of the perfect fourth, made apparent in the opening melody, is the movement’s primary interval melodically, harmonically, and in terms of form.

Throughout the Suite and the Concerto, Hétu’s tendency to integrate musical material is evident. His use of motivic manipulation and development is a great example of tight, highly unified, organic writing. This quality in the music gives a performer many possible avenues to investigate. Glenn Gould [viii] used to say “To every man his own Bach”, suggesting that the music of Johan Sebastian Bach offered many possibilities to a performer, making various convincing interpretations possible. This sentiment rings true in regards to Hétu’s works. In a 2002 interview with Eitan Cornfield for the documentary Jacques Hétu-Portrait (CMC, 2002), Canadian flutist Robert Cram addresses this quality in Hétu’s music:

What demands does a composer make of me, as a performer, in interpreting their music? …Technically, Jacques writes music that is demanding…and, as a performer…he gives you material, and then you’ve got to go to work! There’s enough room in it for many decisions, for many ways of performing that music, for many different interpretive possibilities. It’s a whole world of fantasy that he opens up in effect for the performer, and there is enormous pleasure in that.

One cannot help being attracted to the many wonderful facets of Hétu’s music. And while trying to remain sensitive to these qualities, I must confess that in making this recording, I could not resist highlighting some of the unifying, and lower level structures at the foundation of the Suite and the Concerto. Though only a thin veil covers the musical background, the motivic/harmonic cyclical aspect of these works as a whole can easily go unrecognized. Perhaps it is fair to say that the framework is always heard, but often waiting to be noticed. Or as Mr. Grimes stated, “There is more here than is apparent to the casual observer…”

Footnotes:

- Scott Tennant, Pumping Nylon (Van Nuys, California: Alfred Publishing

Co., 1995), p. 59.

(return to source)

- Correspondence between Françoise Haug-Budry (Montréal,

Canada) and Dutch guitarist Han Jonkers (www.hanjonkers.com).

(return to source)

- Decca DL 983.

(return to source)

- Matthey, Jean Louis et Louis Daniel Perret, Catalogue de l'œuvre

de Hans Haug (Lausanne, Bibliothèque cantonale et universitaire,

1971).

(return to source)

- Angelo Gilardino, “Segovia Foundation Treasure Trove” in

Soundboard (Fall/Winter 2001/2002), p. 19.

(return to source)

- Jacques Hétu, Concerto pour guitare et orchestre à cordes,

Op.56 (Saint-Nicolas, Québec: Les éditions Doberman-YPPAN,

1996).

(return to source)

- David Grimes, “Hétu, Jacques: Suite, Op.41” review

in Soundboard XV, 3 (Fall 1988), p. 251.

(return to source)

- Glenn Gould recorded Hétu’s Variations pour piano,

Op. 8 in 1967. His writings concerning Hétu’s music

can be found in: The Glenn Gould Reader, ed. Tim Page (New York:

Vintage Books, 1984), pp. 204-207.

(return to source)